Explore the best of Prague’s 20th century architecture with Adam Štěch

Share

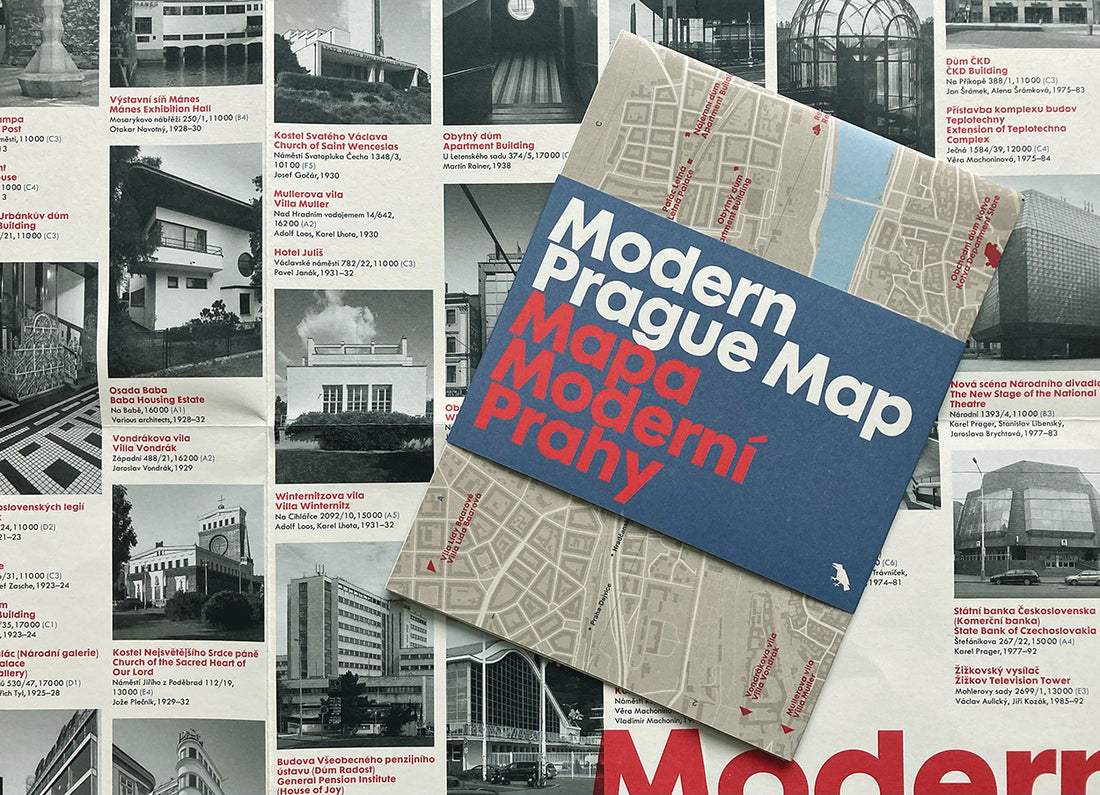

Prague local Adam Štěch (born in Děčín, Czech Republic, 1986) has been active across design, architecture, fashion and graphic arts as a theoretician, journalist and curator since 2006. He founded creative collective OKOLO in 2009 with graphic designers Matěj Činčera and Jan Kloss, and he is editor of Prague-based design magazine Dolce Vita. Here Harriet Thorpe meets Adam, editor of our Modern Prague Map, to find out some travel tips, discoveries and where to find the city’s finest green Cuban marble interior…

What is your personal connection to the city of Prague?

I arrived in Prague in 2005 to study Art History, and I have stayed here ever since. Prague is now my home – my place of work and fun.

How did you become interested in modern architecture and design?

When I was about 17 years old, I saw a particular Impressionist painting in a book on my parents bookshelf. From that moment, I realised I loved art, and since then I devoted my time to researching art, mainly painting and sculpture. Slowly I became more and more interested in architecture and design, because these disciplines of art were closer to me as a person, admiring objects around me. I started to study Art History at Prague's Charles University, but it was very academic and focused on Baroque and Gothic mostly. So I studied modern architecture and art independently, and it became my biggest passion and also my work.

What makes the 20th century architecture of Prague so interesting?

Prague was always at the crossroads of history. At the beginning of the century, Prague was part of Austro-Hungarian Empire and had a very good connection to Vienna. There was huge influence from the Vienna Art Nouveau, which began a culture of innovation in the city that continued over the following decades. After Art Nouveau, Cubism was the new defining style and Prague was the only place in the world where Cubism was truly translated into architecture.

After 1918, when Czechoslovakia was born as an independent country, there were big national ambitions. These were reflected in architecture, mainly in 1920s and 1930s modernism which became the dominant movement. After the Second World War, Communism came to power and architecture declined. But even during this period, some interesting and innovative buildings were built. So Prague is a really wonderful cocktail of styles and movements of the 20th century – which you can experience all over the city, with a backdrop of amazing history and beautiful Gothic and Baroque architecture.

We just arrived in Prague and unfolded the map. Where should we begin, and where will we end up by the end of the day?

If you arrive to Prague by train, ideally, you can start at the main station (above) which is featured on the map. Take the next two hours walking around the centre, where you can explore really iconic buildings quite close together around Wenceslas Square. I would recommend to go for lunch at the Grand Café Orient, the beautifully restored Cubist café in the Black Madonna House (below), which is also on our map.

In the afternoon, I would check out Vinohrady and Žižkov which are now trendy districts, mainly around the Jiří z Poděbrad Square connected to the Josip Plečnik church. After that, I would head to the Baba Housing Estate and from there to Letná, where you can explore many modernist buildings from the 1930s, among others. This is another very popular area with many hip cafés and bars – a perfect place to stay for dinner, for example at the Lokál Nad Stromovkou pub.

Can you pick one building from the map, and tell us something surprising or lesser known about it?

I would pick a very classical one – the New Stage of the National Theatre (above), designed by Karel Prager with an absolutely amazing glass facade by glass artists Stanislav Libenský and Jaroslava Brychtová. Inside this Brutalist building, you can find interiors completely clad in green Cuban marble. This marble was delivered to Prague in many tonnes as a present from Fidel Castro for Czech Republic’s help developing socialism in Cuba.

Which architect’s work from the map do you most admire and why?

Very hard to say. But in general, I like the architects of the late 1930s Modernism, who transformed rigid Functionalism into more sensual and organic forms. Architects such as Martin Rainer, Eugen Rosenberg or Vladimír Grégr.

In your opinion, what makes a building “iconic”?

Probably how the building makes a presence in its environment and how important it is in the developing of some particular movements or historical period.

The Modern Prague Map includes a map, an introduction to Prague’s 20th century architecture by Adam Štěch, original photography by Tomas Souček and details of fifty buildings representing the city’s remarkable array of styles: from Cubism and Modernism to Brutalism and Postmodernism. Available to purchase here.