Goldfinger’s storied Trellick Tower housing in London

Share

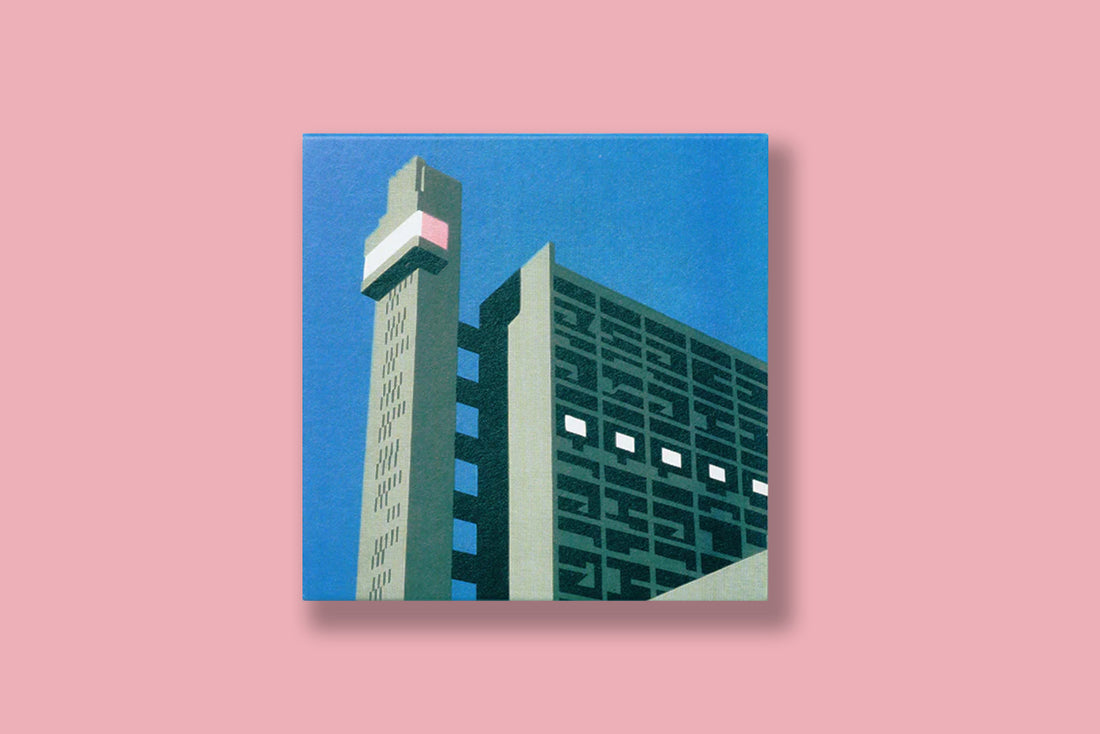

The first in our new Modernist Matchbox series features an illustration of Trellick Tower by Paul Catherall. Here we explore the relevance of the building to architectural and social history. Strike a match to spark a debate on why Modernist housing matters today!

Towering housing blocks in Britain are not all equal. It may strike you as strange, our obsession with them here at Blue Crow Media, however in the era they were built, they were innovative, technological feats (kind of like AI today). They offered people well-insulated and functionally planned homes in the sky – with incredible views across the city. After years of living in leaky terraced houses of bygone eras, Modernist housing was relatively refreshing for residents.

Trellick Tower is possibly one of the UK’s most famous and storied high-rise concrete housing towers. It has a fascinating history, which continues today. It was commissioned by the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1968 to replace a patch of Victorian terraced housing, during the post-war period when social housing was in great demand. On a relatively small plot on the Edenham Estate, its 31 floors hosted 217 homes with balconies. It opened in 1972 as the tallest residential building in Europe.

As global populations rise, as well as that of London (nearly a megacity of 10 million) we increasingly have to find more efficient ways of housing people without taking up too much land, which needs to be preserved for nature and its ecosystems. High rise residential towers such as Trellick started off this conversation, which is still very – in fact, even more – relevant today with a higher global population and increasing pressure on our earth which is causing climate change.

The history of Trellick Tower

Today, Trellick is considered one of the most superior Brutalist towers in London. Its design by Hungarian-born architect Erno Goldfinger was inspired by the work of French architect and founder of ‘Brutalist architecture’ Le Corbusier. The latter architect was the designer of the Cité Radieuse housing concept, which he brought to life in France and Germany creating vertical cities of housing, streets, amenities (such as shops, schools and cafes) and services (from clever waste managements systems to laundry rooms) – everything you could imagine you might need for daily life could be found in your building.

Blue Crow Media's Modernist Matchbox No1, picturing the Trellick Tower illustrated by Paul Catherall

Architect Goldfinger fled from the Nazis in 1934 and moved to England, where he settled and married. Before designing Trellick Tower in West London, he designed Balfron Tower in East London (1965-68). The pair of towers are very similar, yet have very different stories (and storeys: Balfron at 26, Trellick at 31). After Balfron was built, Goldfinger famously moved into the penthouse apartment (becoming inspiration for Ian Fleming’s 1964 villain Goldfinger and the 1975 novel High Rise by JB Ballard). He invited residents over for cocktails to ask them questions about life in the building – what was successful and what could be improved. He would use this feedback to design Trellick Tower.

Trellick's functional interior design

So what’s so special about Trellick Tower? What makes it so superior to other high-rise residential buildings? Well, the building offered the largest apartments of its time giving residents lots of space, daylight and views; the two level apartments stretch the whole way through the building bringing in daylight and opening up views of the city on both sides – to achieve this, the main entrance corridors sit on every third floor. Additionally, there were a number of clever interior devices; sliding doors to save space, double glazing, pivoting window systems and integrated fans. Each flat has huge windows and balconies. A connecting service tower next to the apartment tower contained a communal heating system and water storage tanks, a lift and staircase. In neighbouring buildings on the estate, there were shops, offices (including Goldfinger’s own), a youth centre and doctor’s surgery.

Amidst all of these functional life-improving additions, I don’t know if you agree, but compared to its contemporaries, we think the rough concrete Trellick Tower is pretty majestic. Its sculptural form features slitted windows inspired by a medieval castle and its colourful glass foyer windows create a sunny welcome to the building. Brutalism expert John Grindrod describes Goldfinger’s towers as ‘muscular’, ‘brawny’ – made ‘from the roughest of brown concrete – like a shingle beach at low tide’.

Though it had a uniquely captivating form and good intentions of creating a utopian community, it wasn’t long until unfortunately it garnered a bad reputation and the nickname ‘The Tower of Terror’. Its communal corridors and staircases attracted crime and anti-social behaviour. In the 1980s, the new ‘Right to Buy’ policy allowed social tenants to purchase their apartments privately. Residents then set up an association to address problems and building improvements – a 24-hour concierge service, new lifts, a playground, a new heating system. Government funding for a £17 million renovation was secured. The wider local area started to gentrify and in 1998 Trellick Tower gained Grade II* listed heritage status.

The meaning of Trellick Tower today

When the building reached its 50th anniversary in 2022, it was celebrated as a landmark of British Brutalism. There were film screenings of High Rise (2016), V for Vendetta (2005) and Demolition Man (1993); a panel discussion between architects and social campaigners at the Design Museum; an exhibition of Trellick-inspired artworks by over 30 artists and more. Many creative people have responded to Trellick; take photographer Nicola Muirhead’s photography series that captures the current residents; artist Paul Catherall who has illustrated its graphic form included on our new matchbox; or the architects who have redesigned the apartments, often leaning into their Brutalist identities (like this one by Buchholzberlin). Architectural photographer Simon Phipps, whom we have been fortunate to work with on a number of maps, has an excellent collection of photographs of Trellick Tower here.

Yes, residential towers must be successful in creating warm, dry and functional homes for residents and they must be successful in forging healthy communities, but because our world is evolving all the time, the concept of a ‘successful home and community’ is too, alongside policy change, technological innovation, social dynamics. Perhaps the role of an architect is to create an open-ended framework that can welcome change over time – a strong sturdy building with a tough exterior and interior (and a timeless silhouette for the city), perhaps the hallmark of success is a residential tower that inspires a celebration of its community after 50 years, and when that same community is also invested the future of its next 50 years too.

Our Trellick Tower-inspired matchbox is available here.